by Jacqueline Steincamp

This landmark article by renowned New Zealand journalist and author, Jacqueline (Jackie) Steincamp (1927-2024), was first published by the New Zealand Listener on 19th May, 1984 [1]. To mark the 40th anniversary of its publication, I have digitised Jackie’s original 3,000+ word text, so that this important piece of history becomes accessible to a new generation of readers. Sadly, Jackie passed away in January 2024, at the grand age of 96 [2]. The full text of her original article is therefore reproduced (below) with the kind permission of her son, Hugo Steincamp.

~ Tui Tapanui , The Tapanui ‘Flu Blog (19th May 2024)

A ONCE-BURLY FARMER in his forties sits through the nights on a kitchen chair, elbows on the table — so that nothing, but nothing can touch his super-sensitive upper torso …

A young mother is so debilitated that she can’t walk a city block, can’t hold a cup in her hands, can’t remember her name …

A nine-year-old boy, racked with pain almost too weak to walk, is rocked to sleep nightly in his parents’ arms — if he sleeps, he’s afraid he’ll die …

A 14-year-old swimming rep can barely paddle across the pool…

A country woman, ill herself, and with ill children, promises to write a book one day. She’ll call it To Hell — and Back…

That’s Tapanui flu, Otago mystery disease, Royal Free disease, post-influenzal depression, myalgic encephalomyelitis, M.E.

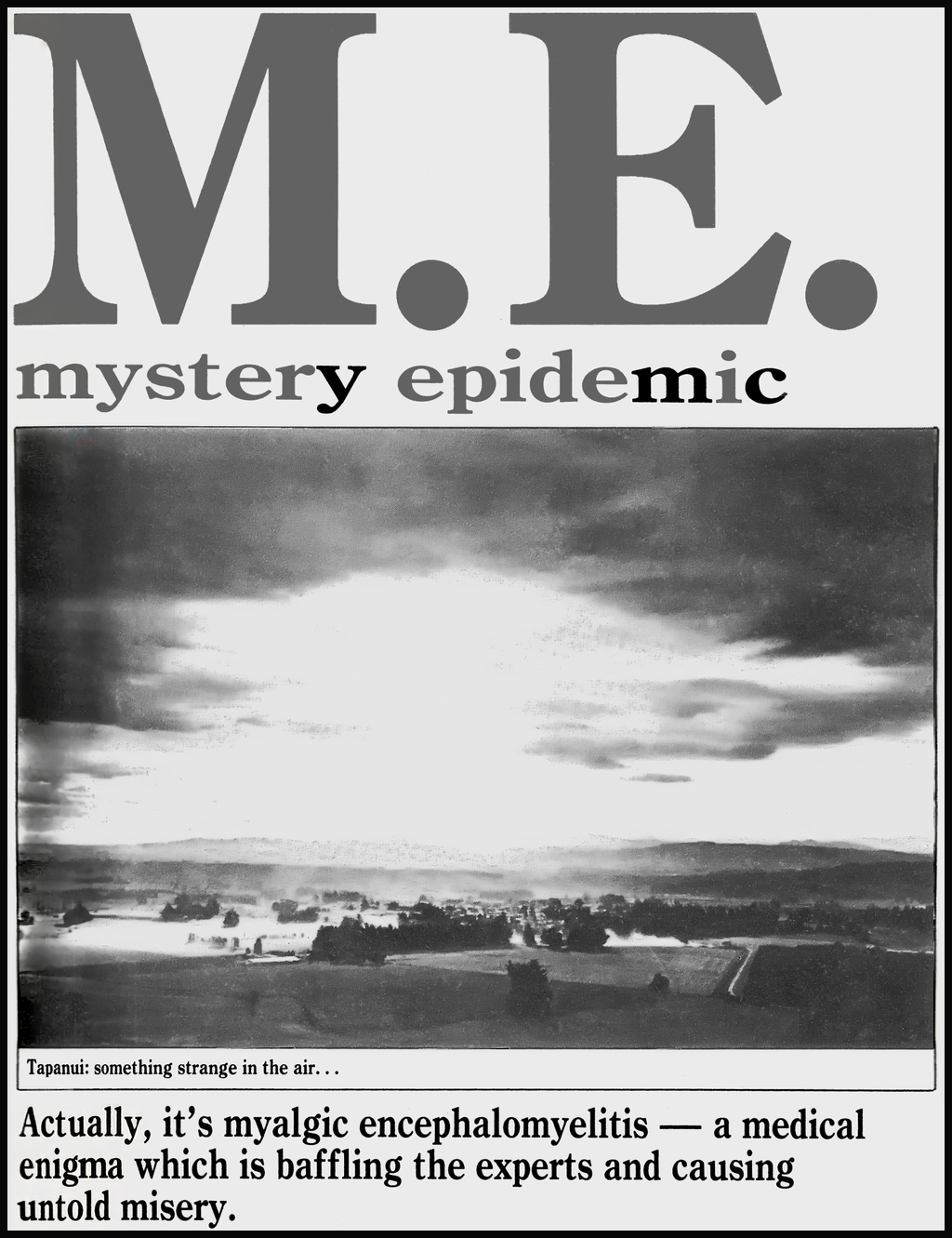

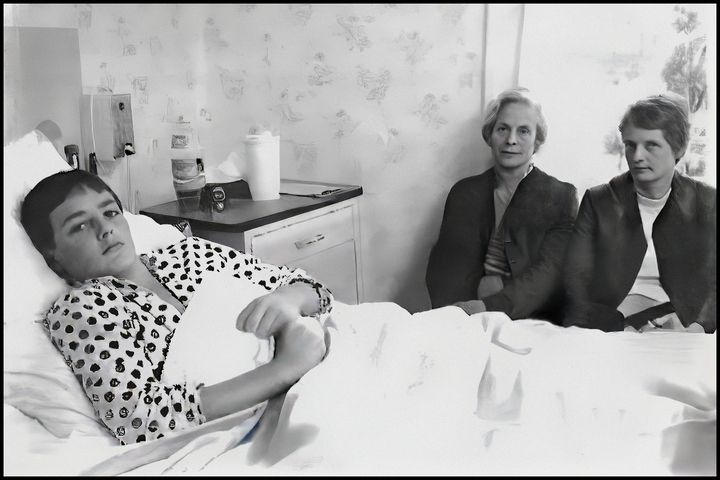

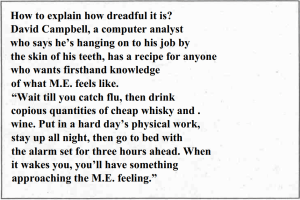

“I’ve been off school for most of the term … I just get so tired … and I was hoping to make the First XV this year. The doctor put me in hospital for observation – I’ve been getting chest pains – and for a rest-up from the effects of M.E.”

Dean McElrea, 16, schoolboy, Tapanui. [Photo: Bruce Foster, NZ Listener]

Whatever it’s called, it brings human tragedy, family crises, ruined careers and financial hardship. It often hits high achievers — people who push themselves hard to obtain the results they want.

A few people have had it for 20 or 30 years. It is by no means new.

Called “benign” because it doesn’t kill, its symptoms can be so severe, so endless, so unexpected, that sufferers almost wish it did. Some have committed suicide when their doctors told them there was nothing wrong with them.

More than 60 symptoms have been noticed in the M.E. syndrome. They affect all parts of the body, from the head to the toes, and all body systems, including the brain. Myriad symptoms, masquerading as those of totally dissimilar conditions. No wonder both doctors and patients are confused.

Interviews with 14 sufferers revealed a wide range of apparently unrelated and often bizarre symptoms. Most prevalent were aching and weak muscles, extreme tiredness, acute chest pains, joint pains, irregular heartbeat, breathing problems, night sweats, violent muscle twitches and gastric and urinary upsets — one person had green urine.

Circulation was affected, with faces, hands and feet often going cold, white and clammy. Or becoming red and burning. The temperature was often sub normal.

Sleep problems, sore throats, splitting headaches, nausea and vomiting were common.

Ringing in the ears, or a hearing disturbance (always of a temporary nature) and vertigo and dizziness were noted.

Vision often became so blurred that reading was impossible. In any case, mental confusion and loss of memory made it difficult for people to concentrate sufficiently to take anything in.

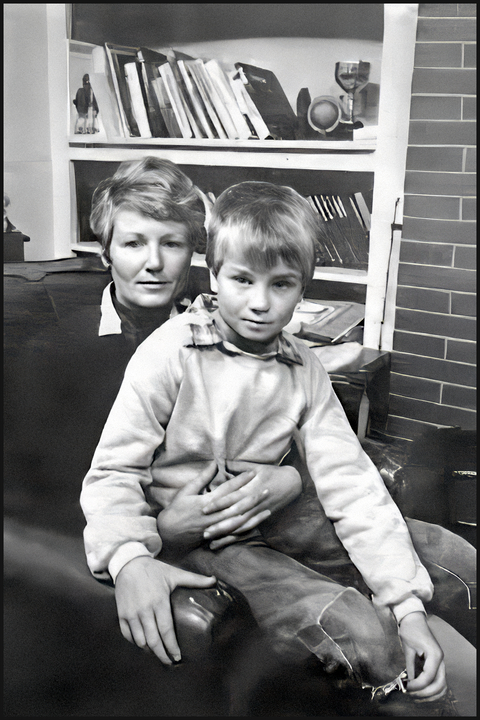

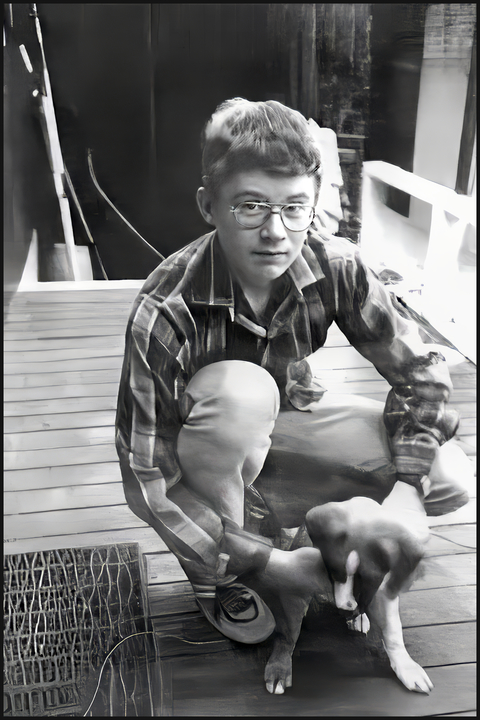

For months Blair was rocked to sleep in his mother’s arms. He was afraid that if he slept, he’d never awaken.

Blair Robertson, 9, Tapanui. (Mother, Jennifer Robertson). [Photo: Bruce Foster, NZ Listener]

Some people had periods when the skin in various parts of their bodies was so sensitive that they could not bear to be touched.

Hanging like a dark cloud over the entire syndrome of symptoms was “a dreadful sense of depression and impending doom”, and a total feeling of being devastatingly unwell.

A survey carried out by the Otago Medical School showed that the clinical picture in the majority of the 70 patients studied is entirely consistent with the diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis. 33% had long-term illness lasting two years or more; 73% had long-term fluctuations in that they felt unwell for days, weeks, or months; 63% felt unwell from one hour or day to the next. All thought the periods of unwellness were related to activity or exertion, and that improvement was usually brought about by rest or sleep.

The survey concluded by saying that there is no positive diagnostic test and no known treatment, although dealing with allergies may prove to be the ultimate answer.

M.E. is one of the growing number of diseases which gain a hold only on those with faulty metabolism and weakened immune responses.

It thus has the widest implications for Western medicine, challenging doctors to ask whether the difference between disease and health may not be just a matter of germs, drugs and surgery, but whether disease happens when something goes wrong in the body to permit germs and viruses to invade it.

The first recorded epidemic was in Los Angeles hospitals in 1934. Since then, there have been about 50 epidemics, three at military bases, eight at hospitals, two in Iceland, three in Southern US states, two in Australia. One of the latter was the 1976-77 epidemic in Sydney in which Toni Jeffreys, author of The Mile-High Staircase and this country’s best known M.E. sufferer, became a victim.

Jeffreys’s nightmare condition is shared by an unknown number of New Zealanders – unknown because it is not a notifiable disease. She says that first enquiries to the Australia and New Zealand Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Society’s Auckland branch are now well into their second thousand.

How many might there be in the country? A Cambridge GP, Ricky Gorringe, who is interested in the relationship between food allergies and the M.E. syndrome estimates 10,000 acute cases. “Probably as many again are hidden chronic sufferers,” he said. He bases these figures on the numbers of patients with M.E. syndrome symptoms presenting to Cambridge doctors – and extrapolates them nationwide. “If each of the country’s 1600 GPs are seeing an average of 6 cases each, that’s a figure around 10 thousand.

“Cases are inclined to be grouped in time-clusters when there’s something around that hits their immune systems. One group dates back around 22 years, and there’s another group from the Russian flu epidemic in 1976,” he said.

It is in Otago that M.E. seems most prevalent. With over 1000 estimated cases, the localised outbreak is among the world’s largest. A substantial number of cases date back to 1978, when there was something of an influenza outbreak. But only a few of the sufferers interviewed recall having flu. Some said they simply felt off-colour for a while, or had swollen glands.

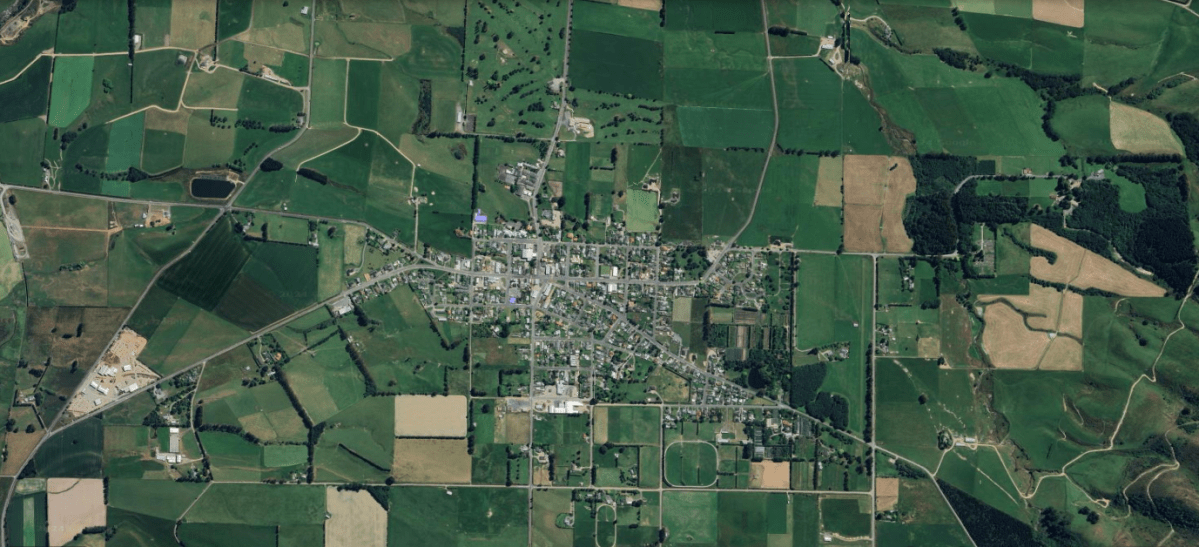

Tapanui – that’s where it’s hurting most, and you could well ask why. Pure air, beautiful countryside, prosperous farms … it’s hard to believe that an illness so malevolent and insidious could stalk such a peaceful, idyllic place. Stress from floods, perhaps?

Peter Snow, the Tapanui GP, has apparently been seeing about one new case a week since 1980, according to his locum, John Shepherd. The first cases appeared around 1978.

Shepherd estimates there are between 300 and 700 M.E. cases in the 3000-odd practice intake. He is seeing between one and two suspected new cases a week.

It is striking at all ages, at both sexes. 30 children at Tapanui’s Blue Mountains College (roll 350) went down with it last year. This year, 10 weeks into the first term, another six are affected.

While college principal Graham Dee feels M.E. has almost become an occupational hazard of life in West Otago, he doesn’t think it is affecting the spirit of the community. Dee, who moved to Tapanui three years ago, has two children with the M.E. syndrome. The youngest boy has been unwell for two years.

Dee is convinced that the students affected are not manufacturing symptoms so that they can skip school.

“It has hit youngsters who are outstanding sportspersons as well as the good scholars. It hits them so hard they are pleased to be back at school. They get thoroughly fed up with being unwell.”

Dee feels that the youngest children seem to be the worst affected. Some become very ill indeed.

“We encourage parents to give them the maximum amount of rest before letting them come back to school. Some came back too soon, and they relapse within the week.”

George Arthur, guidance counsellor at the Blue Mountains College, has a wife, a son and a daughter who have the mystery disease. Not surprisingly, he feels that the situation has reached crisis proportion in Tapanui, with many isolated parents struggling to cope with multiple symptoms — and possibly several family members affected concurrently.

Arthur thinks that one of the most unfortunate aspects of the illness is that it has become a joke. “People laugh when you say you’ve got Tapanui flu.”

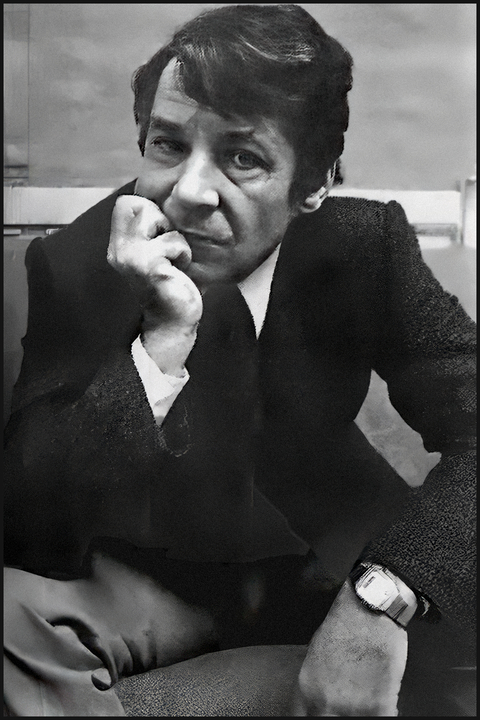

Dann was off school for two terms last year and most of this year. He spends his mornings sleeping and just poters around in the afternoon – he does a bit of schoolwork and takes his dog for a walk if he’s feeling up to it.

Dann Arthur, schoolbuy, Tapanui. [Photo: Bruce Foster, NZ Listener]

Even though they might be considered to be in the heart of the action, some of the Otago doctors interviewed doubt that that the viral cases they are seeing are M.E. Others report no significant change in the type of cases presenting.

“Our practice is watching out for M.E. syndrome, and we’re just not getting any cases,” comments Dr Peter Fettes, a GP in a large medical centre in neighbouring Gore. “We’ve only had one patient who we feel may have M.E. — a woman who’s had neurological symptoms for about six months.”

Yet another Gore GP, who did not wish to be named, had a completely different view. He is worried by the number of strange viral cases — and the possibly mutating viruses. “I am sure these are genuine illnesses, and I am feeling very helpless about how to treat my patients.” This doctor speculated in high local levels of depression and group communication on a low subconscious level which may be affecting the body’s ability to repair itself.

Dr David Cook of Owaka says it’s possibly influenzal depression.

“There were about 150 cases of real flu, and you’ll appreciate that’s very rare, which presented to our medical centre some years ago. About one third of these had various lingering symptoms, similar to those of the M.E. syndrome. We treated them for depression, and they recovered,” he said.

148 of Dunedin’s M.E. sufferers (including three families each with at least three children with M.E.) are being informed, comforted and “kept sane” by a support group headed by Peter Bradshaw, David Campbell and Edna Sizemore. Support group members spoke highly of their sound advice, sympathy and caring attitude.

Bradshaw echoes Toni Jeffreys’s comment that such support groups are saving the health care service thousands of dollars. “We’re doing the work for them, while the Health Department fiddles while Rome burns,” he said.

During the two years Bradshaw has been ill, his marriage has broken up (his wife also is a sufferer) and his income as a clinical psychologist has dropped from around $30,000 a year to just over $5006 in a part-time job in Dunedin’s Environment Centre.

During the first year of his illness, Bradshaw estimates that he spent between $1500 and $2000 on medical bills — $1000 for unnecessary psychiatric treatment, and $600 for an abortive visit to a North Island allergy clinic. He’s been seeing his doctor between 30 and 40 times a year.

“My doctor’s not billing me now — and not all doctors are as generous as he is. Medical expenses are very heavy for M.E. patients, and sickness benefits go nowhere,” he said.

Bradshaw’s case was described by other support group members as one of the most serious they knew. When interviewed, he was having a good period. But, like others, he had no idea how long that would last, or what unpleasantness and pains would next be visited upon him.

A well-built man in his mid-30s, Bradshaw looks as fit as a fiddle at first glance — as did other sufferers interviewed. But on second glance, one picks up a glassy, suffused look in the eyes, a slightly odd cast to the complexion, and — in his case — puffy hands. “My fingers are so swollen I can’t close my fists,” he said.

Medical treatments varied for those interviewed by the Listener. All were told to take things easy for a while, or to have complete bed-rest. Anti-depressants were often helpful. Anti-fungal medications, vitamin Bl2 injections, and calcium for [t]witches were helpful in some cases. Some received antiobiotics.

Many in desperation turned to natural healing and alternative medical techniques such as relaxation techniques, applied kinesiology (touch for healing), dry brush massage, homeopathy and acupuncture (which has often shown up weaknesses in liver and spleen). Several were helped by complete de-sensitising programmes for food allergies at North Island clinics; others found them an expensive waste of time. Rotation diets and an elimination of fats, sugar and processed foods were often helpful.

Although the attitude of the Health Department is described as unhelpful and sceptical by Dunedin sufferers, Peter Bradshaw says that Dunedin doctors have become quite dramatically more aware of the condition during the last five months.

He lists a whole range of particular problems shared by M.E. sufferers:

- uncertainty over diagnosis and continual testing

- feeling disbelieved and neurotic, because GPs are sceptical when presented with new symptoms at every interview

- the organic brain syndromes resulting in depression. woolly mind, and being unable to read or find words

- employment problems — being unable to work for weeks

- economic hardship — inadequacy of the sickness benefit, the time it takes to come through, heavy medical expenses, commitments that cannot be kept up

- loss of self-esteem — feeling totally useless in one’s home and in society

- social isolation — unpredictability of illness makes it difficult to keep to forward arrangements

- marital problems that centre on the extreme irritability of many sufferers.

“Women worry about abusing their kids, and men worry about battering their wives,” he said. “It’s important that both partners understand what’s happening, and work out what to do beforehand. Often the bouts of bad temper only last for a couple of hours, so it’s just a question of someone getting out of the house, or the sufferer moving to another room.”

The efforts of sufferers to seek the cause for their own individual conditions and to work out the most effective treatment appear to be well ahead of the Health Department.

Dr Peter Hinds, Otago medical officer of health, strongly questions the estimate of 1000 M.E. cases in Otago.

“I would think that the figure is something between 50 and 100.”

He bases his estimate on two mailings he has made to Otago GPs, both with very low responses.

As evidence of top-level Health Department interest in new viral strains, Hinds provided a departmental circular dated March 26, 1984 asking medical officers of health for monthly reports on acute respiratory infections and new viral strains. Information is to be gathered from GPs, schools, hospitals and major employers.

How useful will this be? Two GPs laughed at the idea. “How can we let them know when we don’t even know if our patients have M.E.?” one said.

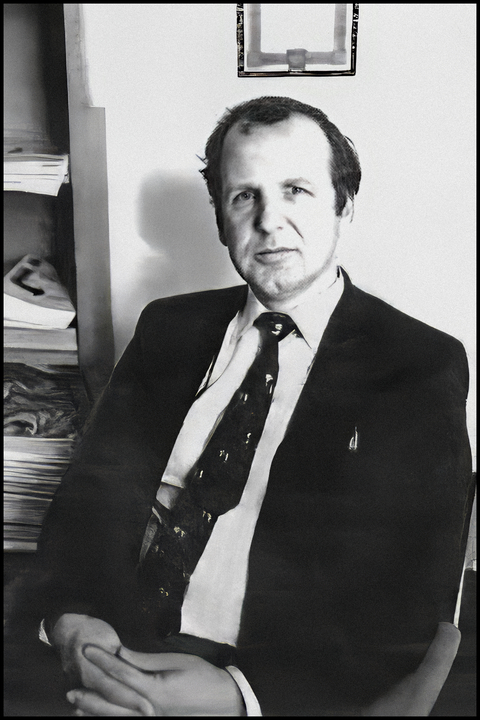

Professor Campbell Murdoch, the genial Glaswegian who has recently taken over the chair of general practice at Otago Medical School, says that information is there for doctors to find, not only material about the illness itself, but also some interesting hypotheses as to what causes it.

Accused by his colleagues of fostering M.E. delusions, he says: “I’m baffled why more doctors don’t accept the condition for what it is, in view of the suffering of the patients, and the extensive medical literature on the subject.”

Where immediate causes are concerned, Professor Murdoch focuses on an invasion of the central nervous system and the muscular-skeletal system by Coxsackie viruses, which may cause a long-term malfunctioning of the immune system.

“Are we talking about an immune system deficiency that is making people chronically unwell for a long time?” he asks. “Or are viruses becoming more sophisticated in manipulating us?”

The immune system is the name given to the extremely complex organisation of glands, white cells (leucocytes, phagocytes and lymphocytes), antibodies, hormones, enzymes, and bacteria which protect the body against potentially harmful viruses, germs and toxic substances.

Its ability to cope depends upon the individual’s general state of health and physical fitness. Immunocompetence may be drastically reduced by fatigue or excessive stress. The condition of the bloodstream is very important to its health.

Opinions differ as to whether M.E. is infectious at the onset only (as in mumps and measles) or also during relapses (as in herpes and acquired immune deficiency syndrome — Aids).

Professor Murdoch thinks that the infectious phase is limited only to the very first few weeks. However, some medical literature considers the possibility of it being infectious during relapses.

A Dunedin sufferer of five years has a foreign-born wife of six months. During this period he has relapsed, and she now has the symptoms.

Whatever the cause, Murdoch feels that developing effective treatment is even more important.

“We must find relief for the people who are actually suffering. They are in big trouble and, in addition, they have the problem of feeling isolated, and of being disqualified from being ill.”

Murdoch bases his estimate of a thousand M.E. sufferers in Otago on the numbers who have been in touch with him — phone contacts with over 100 people in Dunedin alone — and on what GPs have told him.

The future?

Three major problems have to be overcome before M.E. can be dealt with in a manner that’s satisfactory to both patients and professionals, according to Murdoch.

“We need to add to the number of tests that are relevant and that alone can be an expensive business. We need to work out a diagnostic index, and we specially need a rapid diagnostic test.

“At the present moment, it can’t even be diagnosed as M.E. until a patient has had it for about six months. After 18 months, it can be regarded as chronic,” he said.

Recent research in Scotland (where a widespread epidemic is occurring) on M.E.’s principal symptoms of muscle fatigue and weakness, indicate abnormal muscle metabolism. “This seems to be connected with a disorganisation of the utilisation of oxygen and sugar,” wrote neurologist Peter Behan in the June 1983 issue of the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners.

Dr Behan went on to say that it appears that persistent infections of a Coxsackie B were found in some patients — a surprising finding, since these viruses are not considered to be persistent. A further finding was a particular type of impairment of the immune system. A short pilot study of treatment based on these findings is planned for early 1984.

Otago Medical School, which already has research programmes on Candida albicans, plans to measure the presence of immune complexes in deep frozen blood samples from M.E. sufferers, when new techniques are evolved, probably some time this year. If the Coxsackie viruses are widely implicated, it may also be possible to develop a live vaccine for wide use. Another approach may be some type of antidote injected into the bloodstream, says Murdoch.

“What is happening is a good example of a crisis in medicine,” he said. “In 200 years, people will laugh at the doctors of 1984 who thought that healing was all about correcting conditions. The question we have to ask now is how and why alternative healing does help people when traditional medicine fails.”

Toni Jeffreys is in agreement. She thinks that most of the change will not come from within the medical profession, but as a result of pressure from lay people. “As far as we can tell, this is a problem of the last 25-30 years which coincides with a deterioration in the environment. I don’t think that people’s general health will improve until more effort and resources are devoted to improving the total environment.”

References

- Steincamp, J. (1984). M.E. Mystery Epidemic. New Zealand Listener, 107(2310), 21–24. [Listener Article]

- Jacqueline Steincamp Obituary, The Press. [Jacqueline Steincamp Obituary] [Obituary Archived]

Related blog post

Tapanui ‘Flu: 40th Anniversary of the Breaking News that Stunned New Zealand