Thank you to those who read and responded positively to my first blog post, commemorating the 40th anniversary of Jacqueline Steincamp’s “M.E. Mystery Epidemic” article in the New Zealand Listener. I really appreciated the warm reception!

Today is another significant day which I don’t want to let pass unnoticed. On 13th June 1984 – 40 years ago today – the first formal research paper on the Tapanui ‘Flu epidemic was published in the New Zealand Medical Journal.

The paper, entitled “An unexplained illness in West Otago“, was authored by Dr Marion Poore, the late Dr Peter Snow, and Dr (now Emeritus Professor) Charlotte Paul.

Unfortunately, I am unable to provide a hyperlink to a full downloadable version of this research paper, because I haven’t gained all the permissions required under the Copyright Act 1994. (I’ve come close – with permission granted by four of the five current copyright holders – but I’ve not yet been able to make contact with one of the authors.)

However, I have created a new web page to mark the significance of this research paper in the history of M.E. and CFS in New Zealand. This page currently provides the paper’s Abstract, along with the conclusion drawn in its final paragraph. (And if I do eventually gain the final copyright permission required I will publish a link to the full article on this page.)

So, in lieu of providing you with a copy of the research paper itself, I will endeavour to provide an overview and then review of some of its key aspects – hopefully in keeping with the “fair dealing” requirements of section 42(1) of the Copyright Act 1994.

“An epidemic of undiagnosed illness”

The introduction to the paper outlined that Dr Peter Snow, the sole general practitioner in Tapanui, West Otago, “considered that there might be an epidemic of an undiagnosed illness in his practice when a number of patients presented with extreme fatigue and a virtual inability to continue with their employment.”

It was reported that “the majority were young people and school children who traditionally do not regularly attend their general practitioner”. Most had been unwell for about 4-6 weeks before seeking medical attention.

Patient sample selection

Patients were identified by Dr Peter Snow and Dr Marion Poore (who was working as a GP Registrar in Tapanui at the time) “from their memory of patients seen over previous months”. A total of 55 patients were identified as having “a similar fatiguing illness of unknown cause”. All but three of these 55 patients were contacted, and all of those contacted agreed to be interviewed.

To be accepted into the research sample patients needed to meet the following inclusion criteria:

“… (a) onset of illness after March 1982; (b) illness with an acute onset, followed by fatigue and difficulty in performing normal tasks for at least one month; (c) no other satisfactory explanation for the illness.”

Of the 52 patients screened by Dr Poore, 28 were selected as meeting the inclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was having fallen ill before March 1982 (15 patients).

There were equal numbers of males and females. All but three of the patients were under 45 years of age, and 36% of the sample were children under 15 years of age.

Healthy control group

The research undertaken used a case-control study design:

“In order to investigate the importance of environmental factors in the causation of the illness, a control group without the illness was also interviewed. Controls were drawn from the same practise using the family file system.”

In total there were 26 patient-control pairs, who were matched for sex (male/female) and for age (being within 5 years of one another).

“The symptoms are compatible with a viral aetiology”

The paper states:

“Most patients remembered a specific illness about 4-6 weeks before they presented. This commonly involved abdominal pain and some diarrhoea. Some, however, said they had had a flu-like illness with a sore throat and generalised muscle aches and pains, while others complained of severe headaches. All said that after this initial illness they had felt extremely fatigued and had been incapable of a normal day’s activity.”

Several patients had “hepatomegaly or tenderness over the right hypochondrium” and one patient “became jaundiced and was admitted to Tapanui Hospital for care”. In other words, there were signs and symptoms suggestive of liver involvement in some patients.

At least half of the patients reported having had “contact with a similar illness”:

“Sixteen patients (57%) stated that other family members had a similar illness in the past, while fourteen patients (50%) had other relatives or friends who had a similar illness.”

The results of the study confirmed further symptoms compatible with a viral aetiology:

“The majority of cases started with fatigue and gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms. Headache, joint and muscle pains, and mood changes were also common at onset. … More than 80% had a change in mood and sleep pattern, headache, joint and muscle pains, as well as defining symptoms of tiredness and difficulty performing their usual tasks.”

The duration of these symptoms was prolonged, with a relapsing pattern seen in at least some patients:

“The average duration of illness in those six patients who had recovered was five months. However, most of the patients were still experiencing symptoms at the time of our study, and 40% of those had their symptoms for longer than five months. Some patients reported a relapse if they became tired or suffered undue stress.”

The results also revealed that the unexplained illness in West Otago had a biphasic pattern at onset:

“… the pattern of illness was in two distinct phases: the acute phase at the onset lasting about 5 days, followed by a chronic phase.”

The study also found that there was a possible seasonal pattern to the illness, which would also be consistent with a viral aetiology:

“The majority of cases started during the spring and early summer … This timing is in accord with the previous impression of a cyclical disorder presenting most commonly in the early summer”.

However, the authors felt this seasonal observation needed to be treated with some caution: firstly because the reliance on memory to select patients for the sample might have caused earlier cases to have been missed, and secondly because the 4-6 week delay in patients seeking help from the doctor may have caused more recent cases to be missed.

Laboratory investigations

A range of investigative laboratory tests were undertaken:

“All patients had blood taken for a series of tests at the time of the study. Blood count, ESR, liver function tests and the Paul-Bunnell screening test were performed. Serological tests were undertaken for antibody to the following viruses: cytomegalovirus (complement fixation test CFT), Epstein Barr virus (immunofluorescence), coxsackie B1-B6 [CFT), hepatitis A (ELISA) and hepatitis B (RIA).”

The Paul-Bunnell test (also known as the Monospot test) screens for Glandular Fever (also known as Infectious Mononucleosis or “Mono”) which is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. Coxsackie B is one of the more common enteroviruses, and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common herpesvirus.

The authors reported:

“There were no raised titres suggestive of recent infection by cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus or coxsackie B1-B6.”

The authors noted these test results had ruled out Glandular Fever:

“Glandular fever was ruled out because all the cases had a negative Paul-Bunnell test as well as low or absent antibodies to Epstein Barr virus on immunofluorescence.”

However, the authors also noted that there were known limitations with the coxsackie B test, so the negative test results they obtained did not fully exclude coxsackie B as a potential cause for this illness:

“Enteroviruses, particularly coxsackie A and B and echo viruses are known to cause similar syndromes which sometimes run a relapsing course. The complement fixation test for coxsackie B1-B6 infection showed low or absent antibodies in our patients. Complement fixation antibody appears during the course of an infection but may disappear or drop to a low level within a few months, thus our finding makes coxsackie B infection unlikely but does not exclude it.”

Liver function tests were “predominantly normal”, although there were some cases with minor elevations of either liver enzymes or bilirubin levels, changes in serum ferritin concentrations or elevated blood lipid concentrations.

One patient had a weak positive HBsAg (Hepatitis B) result. Hepatitis A antibody was tested for in only nine of the cases, two (22%) of whom returned a positive result. The authors felt this was a usual finding for a population of the age structure seen in the sample.

However, the authors felt that their results still left room for a “non-A” or “non-B” form of hepatitis being a potential cause:

“Viral hepatitis was considered because of the frequent reporting of symptoms and signs suggesting liver involvement: nausea, anorexia, alcohol intolerance, abdominal discomfort, yellow skin colour; the frequent finding an examination of hepatomegaly and right hypochondrial tenderness; and the abnormal liver function tests in some patients. In the absence of markers for hepatitis A or B, a diagnosis of non-A or non-B hepatitis remains a possibility.”

One faecal sample was collected from a patient with acute diarrhoea:

“Campylobacter jejuni was isolated. This man subsequently developed characteristic features of the illness.”

Environmental exposures considered

The authors also considered and screened for a range of possible environmental causes for the unexplained illness.

They obtained the bacteriological survey results from the Department of Health’s routine monitoring of the three water supplies for West Otago – the Tapanui town supply and two rural water schemes. One of the rural water supplies had elevated faecal coliform counts in the month of February 1983 due to a breakdown of its chlorination plant, but otherwise the results were all normal.

Possible food contamination issues, such as those associated with untreated milk or under-cooked chicken were also screened for.

A possible role for selenium toxicity was also considered. Because Tapanui soils were known to be deficient in selenium, farmers needed to provide supplements for their livestock and also apply selenium directly to their pastures. Some of the local human population also took selenium supplements. The authors felt their results eliminated selenium toxicity as a potential cause.

Likewise, toxicity from exposure to other agricultural chemicals was also considered and eliminated as a possible cause.

The table below shows the types of environment exposure that were screened for.

As can be seen in this table, the patients and controls ended up being quite closely matched for most of the potential exposures that were considered. The authors concluded there was no discernible association between having the illness and any of the exposures listed in this table.

“A psychogenic explanation is unlikely”

The possibility of a psychogenic illness, including “mass hysteria”, was also considered – with the authors citing two (very infamous) papers by psychiatrists Dr Colin McEvedy and Dr Bill Beard that were published in 1970. However, the authors dismissed mass hysteria as a cause, stating:

“The epidemiological features are unlike those characteristic of either mass hysteria or other stress-induced illness.”

They did, however, note in the paper that three patients themselves considered that “stress” and having “too much to do” might have been a factor, and that “some patients reported a relapse if they became tired or suffered undue stress”.

The authors therefore noted that:

“… underlying stress may play a part in determining the effect of the illness on the ability of patients to perform their usual tasks.”

But the authors were clear in stating that “ … a psychogenic explanation is unlikely”.

Could this be myalgic encephalomyelitis?

The authors considered whether the illness could be called myalgic encephalomyelitis:

“This name has been used for a variety of outbreaks of illness since 1934. Some early outbreaks have been re-investigated and now look to have been psychogenic [Referencing the two McEvedy and Beard papers of 1970]. More recently the outbreak of fatiguing illness in Scotland, attributed to coxsackie B, was given this label. The most recent descriptions of the disorder include as characteristic features: headache, unusual muscle pains, lymphadenopathy, low grade fever and exhaustion. Some patients have muscle weakness and paraesthesiae. In a minority of cases frank neurological symptoms are found. Nobody reported muscle weakness or sensory disturbance in our study, although we did not enquire specifically about these symptoms. In the absence of neurological abnormalities, and because of the difficulty of making a definitive diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis, we see no justification for calling this illness myalgic encephalomyelitis.”

“A definite disease entity does appear to exist”

The paper then concluded that “A definite disease entity does appear to exist” and noted that:

“We have no evidence that the disease has been confined to West Otago and it may be occurring in other rural and urban practices.”

The final paragraph of the research paper then summarises the findings of this paper as follows:

“In conclusion, we regard the illness occurring in the Tapanui area is a definite entity which has been disabling for those affected. The epidemiological features suggest that it is not psychogenic in origin, nor is it specifically associated with rural living. The symptoms are consistent with a viral aetiology. Further advances in our understanding should come from investigations at the acute stage of the disease and from information about outbreaks in other parts of the country.”

Review

This paper appeared to be a well conducted case-control study, and the authors considered a wide range of possible causations for the illness afflicting the people of Tapanui.

Of note, the paper described a viral pattern to the symptoms , including a biphasic pattern at onset – with an acute phase lasting around 5 days and then a chronic phase. Not mentioned in the research paper is the fact that a similar biphasic pattern had also been noted in a number of previous recognised M.E. epidemics.

Other patterns identified that were also quite characteristic of this being an M.E. epidemic included symptom exacerbations or relapses when feeling “tired”, “doing too much” or experiencing “undue stress”.

But the paper stopped short of calling this myalgic encephalomyelitis – which is a bit puzzling.

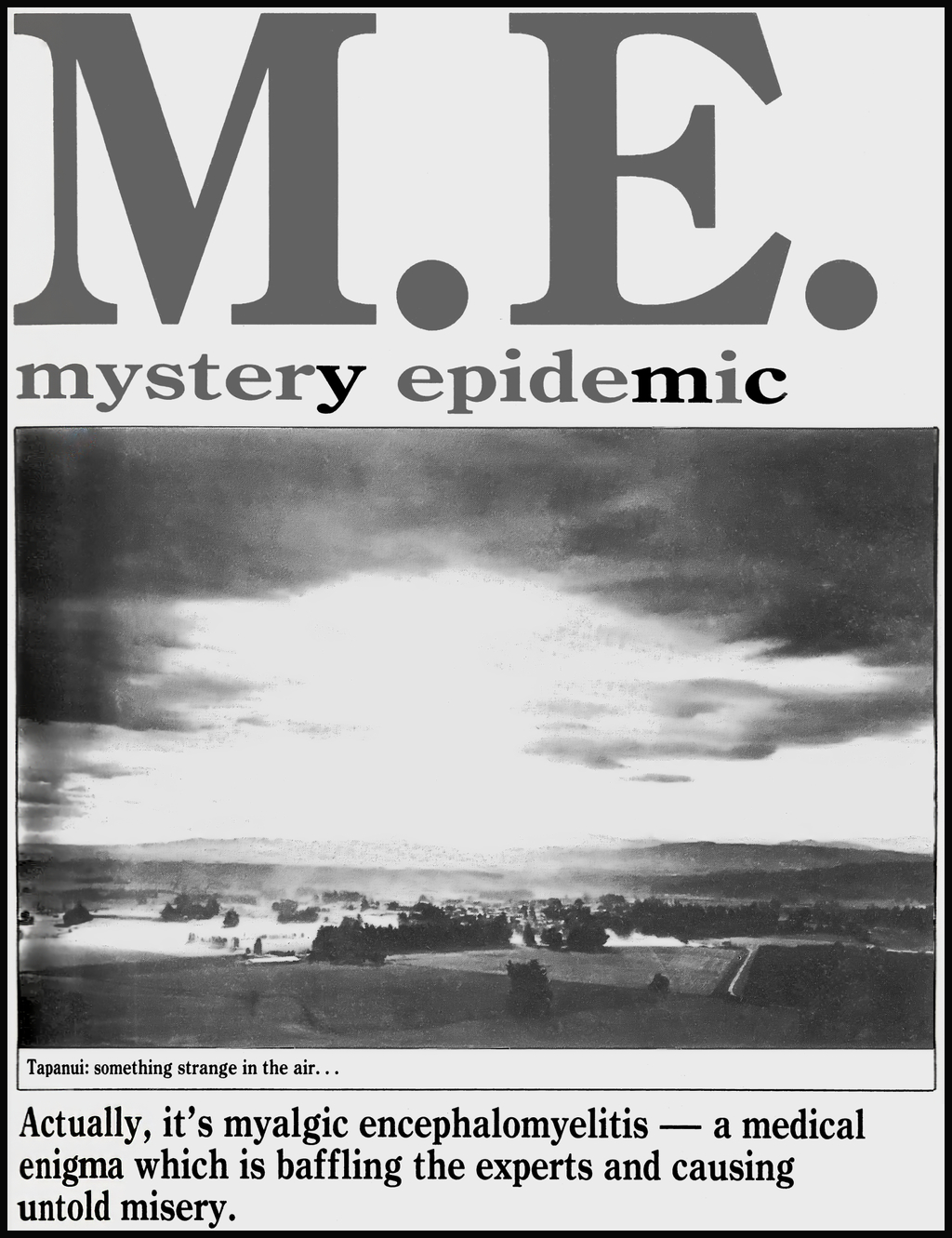

A few weeks ahead of the publication of this research paper an article, written by Jacqueline Steincamp, had appeared in the New Zealand Listener (19 May 1984) about the illness occurring in Tapanui. The article itself was entitled “M.E. Mystery Epidemic”, and it quoted a number of medical professionals who very clearly acknowledged that myalgic encephalomyelitis was, indeed, the underlying condition being seen in the Tapanui outbreak.

And whereas this research paper talked about “the absence of neurological abnormalities” (perhaps referring to a lack of objective neurological ‘signs’, as opposed to a lack of subjective neurological ‘symptoms’), Dr Snow later mentioned that he commonly saw in his patients “… a multitude of odd neurological symptoms such as parasthesias, dysethesias, shooting pains, dead arm, and dead leg, to name a few” (Snow, 1992).

So the authors seem to have chosen to steer clear of the M.E. diagnostic label – and perhaps not all of their reasons for this decision were specified in the paper itself. I have some inklings on possible reasons why this may have occurred, but I’ll refrain from speculating at this stage, and will instead try to gather more factual background information from people who are in a position to know more about the historical backdrop to this research paper.

I also have some questions regarding the timing of this research. In a subsequent paper Dr Snow said this research study was undertaken “During the year of 1983 …” (Snow, 1992). And I’m aware that, in the days before digital “preprints” existed, there could be significant delays between (1) submitting a completed paper to a journal, (2) having it peer reviewed and accepted for publication, and (3) the eventual publication date in the printed journal itself.

Another issue of note is that there was a considerable difference in the number of potential patients who were initially screened for inclusion in this research study, and a much larger number estimated to be enrolled at the Tapanui practice in Jacqueline Steincamp’s “M.E. Mystery Epidemic” article of May 1984. In total 55 patients where identified to be screened for inclusion in this study, whereas Dr Snow’s locum (Dr John Shepherd) was reported to have estimated there were “between 300 and 700 cases in the 3000-odd practice intake” by the time of Jacqueline Steincamp’s investigative report.

So, I’m wondering if perhaps significant delays between completion of the research (likely in 1983) and its final publication date (in 1984) might help to explain the difference. If the research was conducted at an earlier stage of a still-unfolding epidemic, it is feasible that there was a rapid escalation in patient numbers after the data collection phase of this study had been completed – with the epidemic then continuing to gain momentum, both in West Otago and around the rest of the country by May 1984.

Reactions to the published paper

Dr Snow later described the response to this research paper, when it was first published in 1984, as being “intense”:

“The results were published in the N.Z.M.J. The response to the results by the public was intense; they appeared to be aware of the presence of such a disorder throughout New Zealand. The disease was dubbed “Tapanui Flu”, much to the displeasure to the residents of our small community!” (Snow, 1992).

In another subsequent paper (Snow, 2002) he then went into a bit more detail on the responses from the media, the public and the medical profession to the publication of this research paper. But the intense interest of both the news media and the general public in this illness (along with the general reluctance of the medical profession to acknowledge the physical reality of this illness) is a whole other story for another day. So, if you’d like to know more please stay tuned, and feel free to subscribe (below) to receive email notifications as soon as new blogs are posted. And thanks for joining me!

References

Poore, M., Snow, P., & Paul, C. (1984). An unexplained illness in West Otago. New Zealand Medical Journal, 97(757), 351–354. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6589518

Snow, P. (1992). Tapanui Flu (A Quest for a Diagnosis). In B. Hyde, J. Goldstein, & P. Levine (Eds.), The clinical and scientific basis of myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (pp. 104–106). Nightingale Research Foundation. www.nightingale.ca

Snow, P. G. (2002). Reminiscences of the chronic fatigue syndrome. New Zealand Family Physician, 29(6), 385–386.